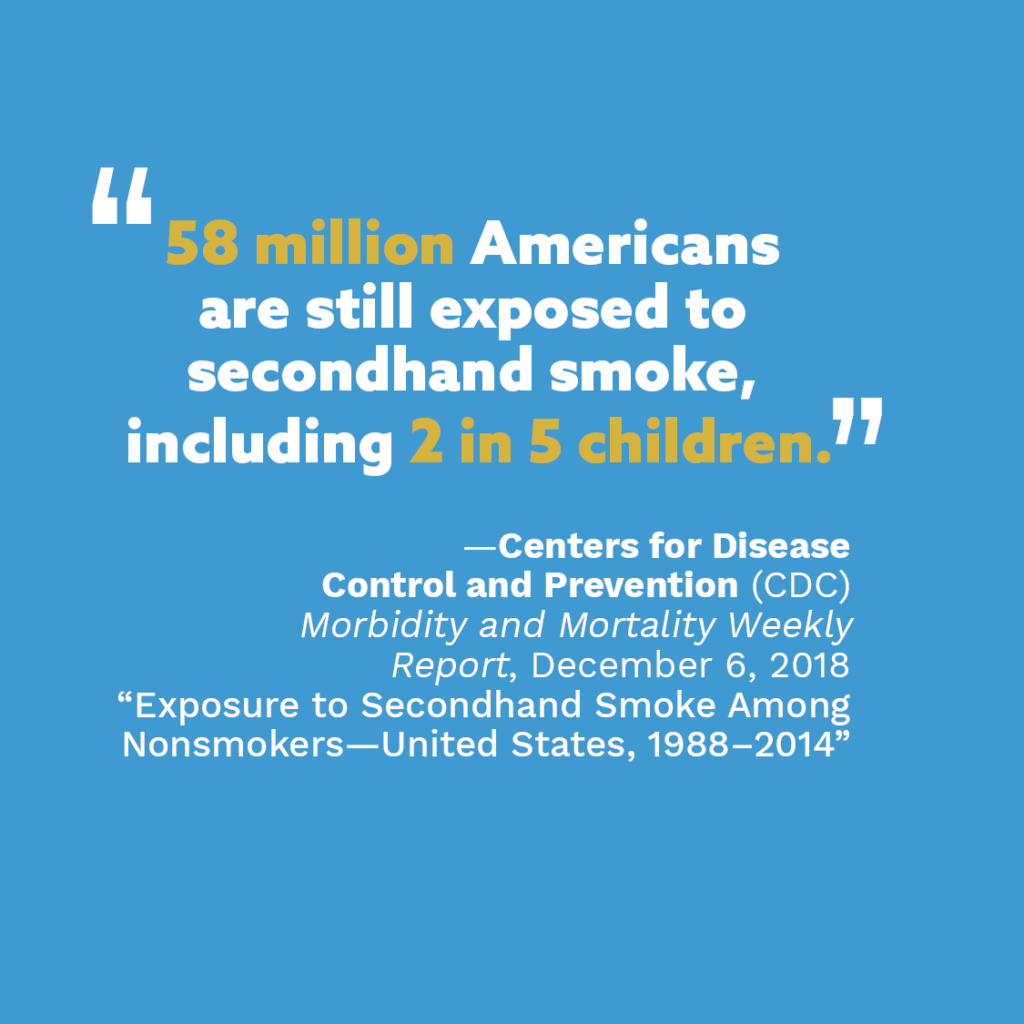

Too many people are falling through gaps in protections from secondhand smoke.

Executive Summary

Our first Bridging the Gaps report, released in 2019, illustrated the dramatic gaps in smokefree protections across the United States with a focus on 12 key states lacking a statewide smokefree law and few, if any, local 100% smokefree workplace, restaurant, bar and gaming laws. The purpose of the report was to increase awareness of the ongoing problem of secondhand smoke exposure for a large cross section of the population and mobilize public health and social justice organizations and individuals to advocate for laws that would close these gaps in smokefree protections.

Since our 2019 report, we faced a global pandemic that was driven by airborne transmission of a virus through respiratory droplets. Many local and statewide smokefree indoor air campaigns were stalled or completely halted. However, we also experienced a global shift in thinking about the importance of shared air and the role of public health policies to protect workers and individuals. For the first time, many in the gaming industry experienced what it was like to operate a 100% smokefree casino; Native American Tribal casinos in particular were early adopters of 100% smokefree policies as part of a responsible response to COVID and reopening safely. Many Tribal and commercial casinos continue to operate smokefree given the popular response from employees and patrons, all the while earning pre-pandemic revenue levels in many markets. In places that did not remain smokefree, workers have been galvanized to advocate for their right to a safe and healthy smokefree workplace. Casino workers in New Jersey and musicians in Tennessee organized and lobbied for equal protections from exposure to secondhand smoke in their workplaces. Expanding public health coalitions to include these new voices and to put them into leadership positions was integral to making change in seemingly stubborn and immoveable places.

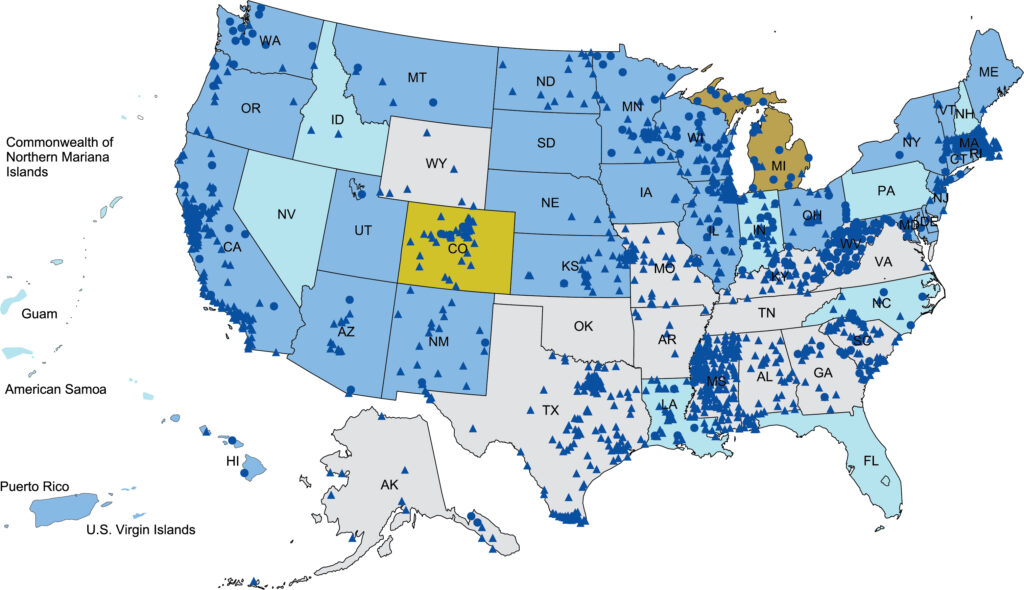

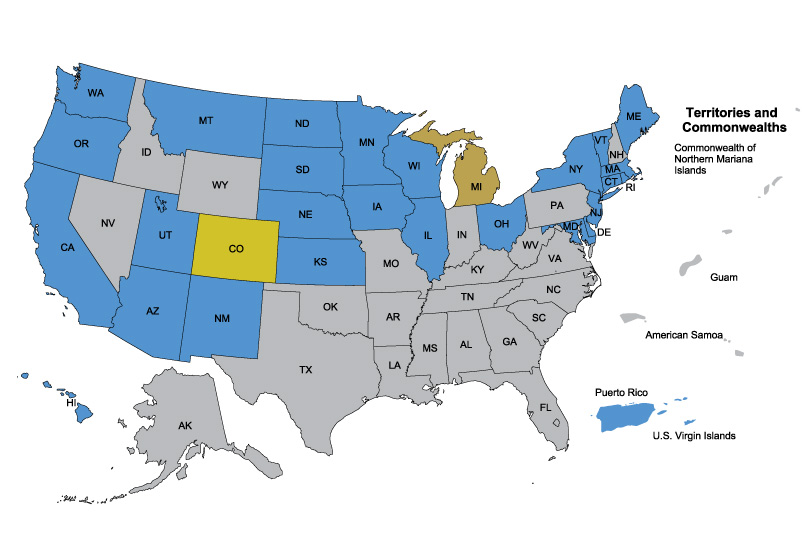

As of April, 2022, 62.3% of the U.S. population is protected by a 100% smokefree workplace, restaurant and bar law, leaving nearly 38% of the population without these basic protections.

WE have an obligation to protect people from the effects of deadly tobacco products like cigarettes and cigars, as well as e-cigarettes and cannabis/marijuana, including the harms of breathing secondhand smoke. There is no safe level of exposure to the smoke produced by burning tobacco, but because many jurisdictions fail to regulate it effectively, secondhand smoke remains one of the leading causes of preventable disease and death in the US. Effective models for creating a smokefree community exist, and places that have adopted them have seen both economic and health benefits.

Smokefree policies are critical public health measures, keeping people out of harm’s way. Unfortunately, these protections aren’t equally available to everyone, and progress in expanding them is uneven. These safeguards have been hard-won, as the tobacco industry lobbies extensively against any restrictions that might reduce their profits. Given this opposition, it is perhaps not surprising that four in ten Americans live in a place that still hasn’t fully protected residents from exposure to secondhand smoke. In many jurisdictions, there are loopholes or exemptions that allow smoking in some types of businesses, placing their employees’ health at risk.

This 2022 edition of the Bridging the Gaps report adds five more state-specific highlights and updates current smokefree protections and policy trends across the United States to pinpoint where we are failing to live up to our commitment to protect everyone equally. In particular, the report highlights places that lack laws that ensure smokefree air, a vital condition for health, and shows which people are least likely to be protected.

No matter where people live, work, or play, they all have a right to breathe air that is free from tobacco smoke, which contains toxins that damage the heart, lungs, mouth, and more. A just society ensures that everyone—regardless of age, race, income, or occupation—is protected from health risks in their environments. By making smokefree policy a part of every health equity toolkit, we can remove a significant source of health disparities and advance greater social justice.

Why are smokefree policies an important public health measure?

Smokefree environments protect people from exposure to the toxins, gases, chemicals, and particulate matter that is released by burning tobacco cannabis/marijuana. By removing these harmful pollutants from the air that we breathe, smokefree policies create immediate and longer-term health benefits. When people in our communities are healthy, we all benefit. Individual well-being translates into greater social, economic, and civic well-being.

Smokefree policies benefit people at every stage of life:

- Smokefree laws reduce smoking in public, which, in turn, means that children and young people see fewer smokers. This makes it less likely that they will take up smoking themselves.

- A study of people who work at bars showed just how important it is that smokefree policies cover every workplace. After the implementation of a 100% smokefree law, nonsmoking employees saw health improvements within eight weeks—including a reduction in respiratory problems such as wheezing, coughing, and shortness of breath, and an improved quality of life for employees with asthma.

- A growing body of research has found that laws making indoor workplaces and public places smokefree are associated with sizable, rapid reductions in hospital admissions for heart attacks. In a three year-long study in Pueblo, Colorado, there was a 27 percent decline in hospital heart attack admissions. In Helena, Montana, there was a 40 percent decline for the 6 months the city enforced its clean indoor air ordinance. In New York State, there was an 8 percent decline. Heart attack admissions in neighboring communities and states experienced no similar declines.

- A study of older adults (ages 65+) enrolled in Medicare showed substantial health improvements after the adoption of smokefree policies, including 20% fewer hospital admissions for heart attacks and 11% fewer hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

- Smokefree laws support current smokers who are trying to quit. Smokefree environments support cessation by providing a social environment that supports smokefree living.

A jurisdiction with a “100% smokefree workplaces” policy ensures that no one must work in a smoke-filled environment that undermines their health and well-being.

As of April 2022, 62.3% of the U.S. population was protected from exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke by laws that cover all public places and workplaces, including restaurants and bars. Twenty-seven states, and two U.S. territories and 1,155 municipalities have these comprehensive smokefree laws.

Casinos are workplaces too: Three municipalities, 19 states, along with Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, and one sovereign Tribal nation have 100% smokefree workplace, restaurant, bar and gaming/casinos law. The Navajo Nation is the first Tribe to adopt such a strong, comprehensive law.

Because these laws have been so successful, many Americans today take smokefree protections for granted—at home, at work, at school, or in public places they typically visit such as restaurants. They may assume that everyone else in the community is also protected and that secondhand smoke is a problem that has been solved.

However, nearly 38% of Americans live in a place that is still not fully protected by a 100% smokefree law. In many jurisdictions, certain types of businesses are exempt from smokefree regulations. Most often, these are businesses that rely on manual laborers, like farms or factories, or hospitality businesses, like restaurants, bars, and casinos. By making white-collar workplaces smokefree while allowing blue-collar workplaces to continue to expose people to dangerous air, our current policies are widening inequalities in health.

If 100% of workplaces were covered by smokefree policies, we could reduce health disparities significantly.

The smokefree movement has changed America–but not for everyone.

“38% percent of the population is not fully protected by a 100% smokefree law, and 20% of this unprotected population lives in a state that preempts the adoption of smokefree laws at the local or municipal levels of government.”

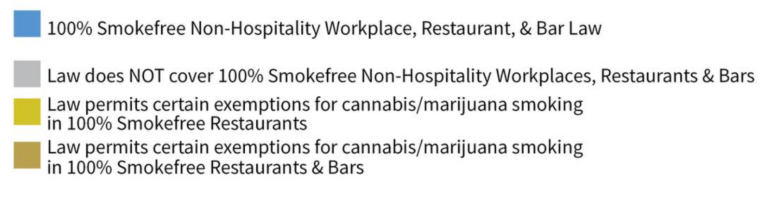

Where people are protected

Local and Statewide Smokefree Workplace, Restaurant, and Bar Laws

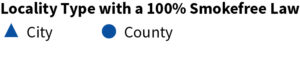

Where people are not protected

Smokefree protections vary significantly from one place to another. Some places have virtually no regulations at all; some protect certain areas or types of workplaces but not others; and others have set policies that ensure that nearly everywhere, even outdoor areas, are free from smoke and secondhand tobacco and marijuana e-cigarette aerosol (aka vapor).

People in the same town can have starkly different exposures to deadly secondhand smoke. Some may never be exposed while others experience secondhand smoke drifting into a child’s bedroom from the neighbor in the next-door apartment, waiting at a bus stop surrounded by smokers, shopping at stores filled with advertisements and promotions for harmful tobacco products, or going to a smoke-filled workplace and having to breathe secondhand smoke every day at levels as high as being downwind from a forest fire. It can mean not having access to quality healthcare screening to catch an illness caused by secondhand smoke early, resulting in more sick days, medical bills, and eventually loss of job from illness and medical bankruptcy.

Those left behind without protections are typically less educated, work in lower paying, blue collar, or hospitality industry jobs, and are people of color. A great deal of work still needs to be done to clear the air for all of us, not just some of us.

it is time to bridge the gap

The spread of 100% smokefree policies has reached a plateau. The 2022 update of this report focuses on seventeen states, which ANR Foundation sees as critical places to rebuild momentum for this highly effective public health measure. By understanding the policy options and contexts in these states, and by supporting and learning from advocates’ efforts to create change, advocates for public health and health equity can continue to make progress.

Residents in Southern and Midwestern states tend to have the fewest smokefree laws and therefore the greatest exposure to secondhand smoke along with some of the highest smoking rates.

Seventeen states that deserve special attention are:

Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia.

None of these states currently have a statewide smokefree law covering workplaces, restaurants, bars and gaming.

Perhaps it is not surprising that nine of the seventeen are noted as the most challenged states in the United Health Foundation’s “America’s Health Rankings” annual report.

Additionally, we should not be surprised that residents of these states are asking for change. There are active educational or advocacy initiatives in each of these states, asking state or local authorities to do more to protect them from the dangers of secondhand smoke. If these promising efforts to go smokefree are successful, the poor health outcomes in these states could be dramatically improved.

Also unsurprising:

Each of these initiatives is being challenged and opposed by powerful, well-financed interest groups, including the tobacco, electronic cigarette, cannabis/marijuana and casino industries.

Some Groups are Less Likely to be Protected from Secondhand Smoke

Justice demands that everyone’s right to breathe clean air is protected, regardless of their age, race, class, or identity. Justice also calls us to actively work toward equality: when we see that some groups are more exposed to secondhand smoke than others, we must work to eliminate the disparities. According to the CDC, some groups are at higher risk of secondhand smoke exposure than others. Inequity linked to class, race, ethnicity, and sexual orientation are also linked to disparities in secondhand smoke exposure.

Clearly, smokefree protections are a health equity issue. they are an important element of making sure that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be healthier.

90% of casino employees are exposed to toxic secondhand smoke in their workplaces.

“According to the Surgeon General, there is no risk-free level of exposure to secondhand smoke, and the only way to protect children and adults is to adopt 100% smokefree indoor air laws and policies.”

- Income inequality is linked to unequal exposure to secondhand smoke.

Housing costs are rising faster than income and earnings, meaning that fewer Americans are buying homes and more are renting. According to the CDC, people who rent in multi-family units (like apartment complexes) are exposed to more secondhand smoke than people who live in a detached home. Two million people who live in public housing that is subsidized by the US Department of Housing and Urban Development are now protected from secondhand smoke, as a result of HUD’s 2018 smokefree public housing policy. This is especially problematic for young children, whose lungs and bodies are still developing. A 2012 study of children who live in homes in which no one smokes indoors found that kids those who live in multi-unit housing had 45% higher levels of cotinine–a marker of nicotine exposure –than children who lived in single-family homes. A 2016 CDC study found that 34.4% of MUH residents who have a smokefree home rule experience SHS drifting into their unit. - Hospitality workers are left out of secondhand smoke protections that white collar workers benefit from.

Gaps in smokefree protections that leave out such venues as casinos, bars, and other service industry workplaces harm the people most exposed to secondhand smoke and typically most burdened with other health and social inequities. - Zoning policies saturate Black neighborhoods with harmful tobacco products.

When local policies fail to limit the number of stores that sell tobacco products in a neighborhood, people see tobacco advertisements more often and rates of smoking in the surrounding neighborhoods increase. More smoking in a neighborhood means more exposure to secondhand smoke. Nationwide, census tracts with a greater proportion of African American residents also have higher tobacco retailer density. This helps to explain why Black nonsmokers are exposed to secondhand smoke than white nonsmokers. Tobacco control policies that limit tobacco retailer density would greatly reduce the disproportionate health burden of secondhand smoke in Black communities. - Discrimination plays a role in exposure to secondhand smoke.

Nearly seven in ten Americans experience some form of discrimination, which contributes to higher stress levels. In turn, chronic stress can alter the brain’s connections, increasing a person’s chances of developing conditions like tobacco dependence. This helps to explain why Blacks, Latinos, and people who identify as LGBTQ2 smoke at higher rates–and why nonsmokers who are part of those communities are exposed to higher levels of secondhand smoke. Efforts to expand tobacco control measures can’t afford to ignore equity issues.

How Can We Close the 38% Gap in Smokefree Protections?

It is time to achieve equity in smokefree protections for all, regardless of geographic region, race, ethnicity, occupation, or economic status. By making smokefree indoor air policies a priority, we can remove a significant source of health disparities and advance greater social justice. Here are important steps we can take to achieve equity in 100% smokefree policies.

Consider smokefree air a social determinant of health.

According to the CDC, an environment free of life-threatening toxins is a vital condition for health. That’s why ANR Foundation believes that secondhand smoke should be considered a social determinant of health. Exposure to secondhand smoke should be a key metric in public health reports, just as tobacco use is regularly included. Doctors routinely ask patients if they smoke, but they do not ask if they are exposed to secondhand smoke. This should change.

Make all workplaces smokefree–with no exceptions.

Smokefree means no smoking or vaping of any tobacco or cannabis/marijuana products indoors, in any establishment, at any time. Many workplaces are now protected, but certain classes of workers are being left behind. For example, at least 90% of people who work at casinos are exposed to toxic secondhand smoke in their workplaces. In some states, this means that a significant portion of workers aren’t benefiting from occupational health and safety standards that others can take for granted. Casinos, race tracks, and other gambling establishments employ at least 175,000 people who work as card dealers, slot machine operators, hostesses and bartenders, floor managers, and cleaning staff. Twenty-one states include gaming establishments in their statewide smokefree laws; three localities also include casinos in their smokefree workplaces laws. Sadly, none of the gaming states with the largest number of employees require casinos to be smokefree, including Indiana, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nevada, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. In addition, many Tribal casinos are not yet entirely smokefree, leaving most Tribal employees exposed to secondhand smoke.

COVID changed the smokefree casinos landscape, with Tribal casinos leading the way. For some establishments, it was the first time they had operated smokefree. Many casinos have sustained the smokefree rules; however, too many have rolled back these life-saving protections.

As of July 2022, there are at least 1,033 U.S. casinos and other gaming properties with 100% smokefree indoor air policies. This number includes at least 157 Indian gaming facilities operating smokefree during the COVID-19 pandemic by their own sovereign policy.

Casinos are workplaces–and no one should be forced to be exposed to secondhand smoke at work. The bottom line is everyone needs to breathe at work. Smokefree workplace protections should be for everyone.

Insist on evidence and integrity when crafting smokefree policies.

Smokefree policies should prioritize public health – not profits–and protections shouldn’t be weakened by loopholes designed by lobbyists. Exemptions in smokefree workplace laws are the result of lobbying pressure from Big Tobacco and its allies, and they affect the lives of real people. For instance, the tobacco industry and casino owners have lobbied for ventilated smoking sections as a substitute for truly smokefree workplaces. According to independent indoor air quality experts, ventilation does not control exposure to secondhand smoke. Since 2010, experts* have agreed that “the only means of effectively eliminating health risk associated with indoor exposure [to secondhand tobacco smoke] is to ban smoking activity.”

* The American Society of Heating, Air Conditioning, and Refrigeration Engineers (ASHRAE) is the international ventilation standards setting body for acceptable indoor air quality. ASHRAE adopted a Position Document on Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS – now referred to as secondhand smoke) in 2010. ASHRAE bases its ventilation standard (62.1) for acceptable indoor air quality on an environment that is completely free from secondhand tobacco smoke, secondhand marijuana smoke, and emissions from electronic smoking devices. No amount of ventilation or filtering can eliminate the health risks of secondhand smoke either from tobacco or marijuana products. Even sophisticated ventilation systems in hospitality settings do not protect people from the health impact of secondhand smoke, marijuana secondhand smoke, and secondhand vapor emissions from e-cigarettes. False claims of being able to “clean” the air by filtration or using other chemicals are not a substitute for clean air.

Evidence presented by independent entities with a mission to act in the public interest can bring greater integrity to the policymaking process. Exemptions in smokefree laws result in social injustice, denying the compelling population-wide health benefit of smokefree laws, such as lower heart attack and stroke rates—to communities already burdened with higher acute and chronic disease rates and their inherent costs.

Secondhand smoke causes 7,000 annual deaths from lung cancer and 34,000 annual deaths from heart disease.

Return power to local communities to create stronger smokefree policies.

Over the last decade, hundreds of local communities have adopted smokefree laws, which not only increases the percentage of the population protected, but sets the wheels in motion for more progress in their states. But in some states, tobacco industry lobbyists have persuaded state legislators to set limits on local governments’ ability to adopt smokefree laws, a tactic known as “preemption.” Preemption at the state level removes a community’s right to enact local smokefree air laws–setting a ceiling on protections. This is especially problematic because action at the local or municipal levels of government has historically led the way for stronger protections from tobacco-related harms. As a result, 20% of the population left unprotected lives in preemption states that do not fully allow for local law development and have not yet shown leadership to adopt statewide smokefree laws. Of the 17 states we focus on, North Carolina and Tennessee have limited preemption provisions while Oklahoma and Pennsylvania are fully preempted from taking local action.

“Preemption occurs when a law passed by a higher level of government takes precedence over a law passed by a lower one. Preemption is a key tobacco industry tactic that removes a community’s right to enact local smokefree air laws. Preemptive state laws set a ceiling, rather than a floor, and do not allow local authorities to enact strong local laws.”

Prioritize smokefree protections in health equity initiatives–and vice versa.

Secondhand smoke exposure and the absence of smokefree protections are related to underlying social and economic factors. Issues of race/ethnicity and other social determinants of health need to be part of the discussion. Underlying factors of social inequity, institutional racism, and the residue of lived experience won’t be magically erased solely through better protections from secondhand smoke. Tobacco control advocates, public health advocates, and health equity advocates should come together across sectors, build diverse networks and coalitions, and create a shared experience through civic engagement. These are all important steps on the path to a more vibrant and livable community for everyone. The call for health equity offers an opportunity to broaden our coalitions and increase our people power. Smokefree air in workplaces, public places, and homes is a compelling issue that brings together a broad spectrum of support—from organizations and individuals representing all walks of life and across the political spectrum that otherwise may not have traditionally worked together.

PROGRESS IN THE SMOKEFREE MOVEMENT HAS LEFT PEOPLE BEHIND

The nonsmokers’ rights movement originated in the 1970s, with nonsmokers asking for separate, nonsmoking areas in restaurants and other public places. At the time, there was little scientific evidence about the impact of what was then called environmental tobacco smoke: the only evidence was people’s observation that others’ smoke caused them discomfort and irritation.

With time, the science increased and studies pointed to the hazards of secondhand smoke on the nonsmoker, and more local communities adopted nonsmoking section policies throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. By 1986, enough evidence had accumulated to support a report from the Surgeon General: “The Health Effects of Involuntary Smoking.” Hundreds of local clean indoor air laws that prohibited smoking in sections of businesses, including airplanes, were adopted through the 1990s.

While nonsmoking section laws were a significant public health accomplishment, it was evident that secondhand smoke drifted from smoking sections into nonsmoking sections. When the Surgeon General concluded that “the simple separation of smokers from nonsmokers was insufficient to protect nonsmokers from exposure to the harms of secondhand smoke,” advocates pushed for stronger protections.

And when the Environmental Protection Agency classified secondhand smoke as a carcinogen–something known to cause cancer in humans–the public began to demand truly smokefree environments. The number of 100% smokefree laws began to increase in the mid-1990s. In 1994, California became the first state to declare all restaurants, bars, and gaming establishments 100% smokefree. Restaurant associations funded by the tobacco industry objected loudly, predicting economic doom. After the policy was passed, restaurants and bars continued to thrive as smokefree establishments, and other cities and states would soon follow California’s lead. Subsequent research on the economic impact of smokefree policies on restaurant and bar revenues confirmed that smokefree environments didn’t hamper businesses, and some studies even found positive effects on the bottom line.

Today, those most likely to experience smokefree environments are predominately white, highly educated and affluent, work in white collar jobs, and live in single-family homes. They may also have more robust health insurance which includes preventative health screenings and tobacco prevention and cessation support. Additionally, they tend to be nonsmokers and may rarely see or experience secondhand smoke exposure in their daily lives.

Smokefree progress takes time and resources...

...especially if groups are committed to including and engaging diverse voices.

This critical work can be accomplished, but it takes time and financial resources to build consensus, engage diverse partners and individuals, and to effectively make policy change.

TIME to create partnerships in a community to build a diverse and powerful coalition. These dedicated community members must be committed to tackling Big Tobacco, one of the largest, most aggressive opponents to strong, life-saving public health policy-making.

TIME to educate the diverse and often marginalized populations still left exposed to secondhand smoke in their workplaces, who may face ostracization, or retaliation, if they speak up in support of a smokefree work environment.

TIME to survey, educate, and mobilize people and organizations who may be focused on other important social justice and health equity issues to build understanding that working on smokefree laws and policies provides immediate health protections, improves health equity, and lays the groundwork for success in other policy areas. Individuals and professionals must be engaged in this ongoing yet ever-changing movement to ensure we have organizational history and understanding, as well as new partners, fresh ideas, and deeper connections with the community.

TIME to ensure policy makers hear the voices of community members who want safe and healthy communities with smokefree housing and work environments.

This time requires financial resources. It takes financial support to conduct community surveys; compensate community partners for their time, effort, and expertise; communicate over various channels and mixed media to various audiences; track and expose industry interference; and convene national, state, and local partners to assure that we all work in concert to achieve our public health equity goals and align strongly against any industry opposition.

This critical work can be accomplished, but it takes time and financial resources to build consensus, engage diverse partners and individuals, and to effectively make policy change.

TIME to create partnerships in a community to build a diverse and powerful coalition. These dedicated community members must be committed to tackling Big Tobacco, one of the largest, most aggressive opponents to strong, life-saving public health policy-making.

TIME to educate the diverse and often marginalized populations still left exposed to secondhand smoke in their workplaces, who may face ostracization, or retaliation, if they speak up in support of a smokefree work environment.

TIME to survey, educate, and mobilize people and organizations who may be focused on other important social justice and health equity issues to build understanding that working on smokefree laws and policies provides immediate health protections, improves health equity, and lays the groundwork for success in other policy areas. Individuals and professionals must be engaged in this ongoing yet ever-changing movement to ensure we have organizational history and understanding, as well as new partners, fresh ideas, and deeper connections with the community.

TIME to ensure policy makers hear the voices of community members who want safe and healthy communities with smokefree housing and work environments.

This time requires financial resources. It takes financial support to conduct community surveys; compensate community partners for their time, effort, and expertise; communicate over various channels and mixed media to various audiences; track and expose industry interference; and convene national, state, and local partners to assure that we all work in concert to achieve our public health equity goals and align strongly against any industry opposition.

“The conditions in the environments in which people live, learn, work, play, worship, and age affect people’s health and well-being. Examples of these conditions include safe homes and neighborhoods, availability of healthy foods, and availability of good health care. According to the CDC, another vital condition for health is an environment free of life-threatening toxins. That’s why ANR Foundation believes that secondhand smoke should be considered a social determinant of health.”

Smokefree means no smoking indoors in any establishment at any time. The tobacco industry and casino industry have advocated strongly for ventilated smoking sections as a “compromise” to going 100% smokefree.

Challenges: Electronic Cigarettes, and Secondhand Cannabis/Marijuana Smoke

Smokefree laws should also prohibit the use of e-cigarettes as well as cannabis/marijuana smoking or vaping to prevent secondhand smoke exposure to the toxins, carcinogens, fine particles, and volatile organic compounds that have been found to compromise respiratory and cardiovascular health.

The secondhand aerosol emitted by e-cigarettes and JUUL is not water vapor. The aerosol is a mixture of many substances, including nicotine, ultra-fine particles, volatile organic compounds, and toxins known to cause cancer. Peer-reviewed, published scientific evidence demonstrates that secondhand aerosol is not harmless; it is a new source of air pollution and is hazardous to nonsmokers.

Eighteen states and Washington, DC have legalized recreational, adult use marijuana; 16 are 100% smokefree in workplaces, restaurants, and bars (AZ, CA, CO, CT, IL, MA, ME, MI, MT, NJ, NM, NY, OR, VT, WA, plus DC), two (NV and AK) have exemptions to their statewide smokefree laws, and one (VA) does not have a statewide smokefree law. Legalized recreational marijuana poses a significant threat to current smokefree protections and to expanding protections. Efforts are underway to establish public use cannabis lounges and cafes, which would lead to employee and patron exposure to this form of indoor air pollution. Secondhand marijuana smoke is a health hazard for nonsmokers. Just like secondhand tobacco smoke, marijuana smoke is a potent source of PM 2.5 fine particulate matter; marijuana secondhand smoke impacts cardiovascular function and it contains thousands of chemicals and at least 33 carcinogens.

See the Individual State Reports and How You Can Help:

Conclusion

ANR Foundation is committed to closing gaps in smokefree protections, applying a health equity lens to the disparities in exposure, and to ensuring that affected groups are engaged in the policy making process. It takes people power to overcome the interference of Big Tobacco and its allies and to redesign systems that force some people to live, work, or play in toxic environments.

“The lessons learned in recent local smokefree campaigns in Louisiana and Georgia, as well as the statewide efforts in Tennessee and New Jersey, and the monumental success in Navajo Nation help illustrate the human and financial resources necessary to engage in a successful public health effort, as well as the opposition we can expect from the tobacco industry and its allies.”

Recommendations for closing the gaps in smokefree protections for all.

Strategically focus and plan for local smokefree workplace campaigns that include all workplaces, including bars and casinos, without exemptions. Never accept weak provisions that leave certain classes of workers unprotected. Do not assume a law can be fixed later. Policymakers may think they have already addressed the issue and view the coalition as weak for not advocating for a strong law the first time.

Engage a diverse group of individuals and organizations, and consider who might bring a unique and powerful new voice. Policymakers expect public health advocates to support smokefree laws; hearing from workers, musicians, veterans, and other key community stakeholders can be more powerful indicators of the need for smokefree protections and the level of community support.

Be mindful of the impact of working on another tobacco control policy before a smokefree policy. One possible consequence of addressing other policies is losing political will for addressing smokefree air; policymakers may think they have already addressed tobacco.

Beware of changing environments and new tobacco products. Electronic smoking devices along with legalized adult-use marijuana/cannabis have the potential to bring new sources of indoor air pollution back into smokefree workplaces or create barriers to going smokefree..

Repeal preemption where it exists, and prevent the adoption of preemptive state laws. As public demand for smokefree environments expands from indoor workplaces to outdoor recreational spaces and into multi-unit housing, always allow local municipalities to address public health policy issues. Anything that prevents future policy development progress should be opposed.

Persevere and stay the course. If initial efforts weren’t successful, try again. The tobacco industry and its allies try to create a sense of futility to demoralize smokefree coalitions to a point where they give up. If a campaign did not result in a strong smokefree law initially, regroup, evaluate what more is needed to be successful, and maintain the position that everyone deserves to breathe safe, healthy, smokefree air.

It is time to achieve equity in smokefree protections for everyone, regardless of their geographic region, race, ethnicity, occupation, or economic status. We call on all who believe in justice and equity to support smokefree air protections.

It's Clear: Smokefree Laws Save Lives

Smokefree laws reduce smoking, increase smoking cessation, and prevent youth and young adult smoking initiation.

Smokefree laws also help prevent heart attacks, stroke, and lung diseases.

Smokefree laws prevention exposure to a known carcinogen, and therefore are part of a strong cancer prevention strategy.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the following individuals for their review and input of the report: Christy Knight, State of Alaska, Tobacco Prevention and Control Director, as well as representatives from the American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation staff and consultants, and with the support of its Board of Directors.

About us

The American Nonsmokers’ Rights (ANR) Foundation is a 501(c)3, educational nonprofit organization, which creates comprehensive programs to prevent the harmful effects of secondhand smoke and smoking among youth and adults. Incorporated in 1984, the organization has more than 30 years of experience promoting prevention and education about smoking, secondhand smoke, and exposing tobacco industry interference with public health policies. Our goals include educating the public about the health effects of secondhand smoke and the benefits of smokefree environments. We work closely with community based partners and individuals in cities and towns across the United States to build support for increasing health equity and improving community health through smokefree efforts. Ultimately, our efforts are intended to create a smokefree generation of Americans that rejects tobacco use and is savvy to tobacco industry tactics.

Sources of data:

Huang J, King BA, Babb SD, Xu X, Hallett C, Hopkins M. Sociodemographic Disparities in Local Smoke-Free Law Coverage in 10 States. American Journal of Public Health 2015;105(9):1806–13 [accessed 2019 Mar 25]

Lee JG, Griffin GK, Melvin CL. Tobacco use among sexual minorities in the USA, 1987 to May 2007: a systematic review. Tobacco Control. Aug 2009;18(4):275-282.

Blosnich JR, Jarrett T, Horn K. Racial and ethnic differences in current use of cigarettes, cigars, and hookahs among lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Nicotine Tob Res. Jun 2011;13(6):487-491

United Health Foundation. America’s Health Rankings Annual Report. 2018.

Guingab-Cagmat J, Bauso RM, Bruijnzeel AW, Wang KK, Gold MS, Kobeissy FH. Methods in Tobacco Abuse: Proteomic Changes Following Second-Hand Smoke Exposure. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;829:329-48.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Respiratory Health Effects of Passive Smoking: Lung Cancer and Other Disorders. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, Office of Research and Development, December 1992.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Major Local Tobacco Control Ordinances in the United States. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph No. 3. Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, National Institutes of Health, May 1993.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Exposure to Tobacco Smoke: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2006.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2014.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Cigarette Smoking and Tobacco Use Among People of Low Socioeconomic Status. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2018.

Tsai J, Homa DM, Gentzke AS, et al. Exposure to Secondhand Smoke Among Nonsmokers — United States, 1988–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1342–1346.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Involuntary Smoking: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 1986.

Drope J, Chapman S. Tobacco Industry Efforts at Discrediting Scientific Knowledge of Environmental Tobacco Smoke: A Review of Internal Industry Documents. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2001;55(8):588-594.

Bialous SA, Glantz SA. ASHRAE Standard 62: Tobacco Industry’s Influence over National Ventilation Standards. Tobacco Control. 2002;11:315-328.

American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation (ANRF). Don’t Buy the Ventilation Lie. 2006.

American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation (ANRF). National Smokers Alliance Exposed: A Report on the Activities of Philip Morris’ #1 Front Group. Berkeley, CA: American Nonsmokers’ Rights Foundation (ANRF), January 1999.

Siegel M, Carol J, Jordan J, et al. Preemption in Tobacco Control: Review of an Emerging Public Health Problem. JAMA. 1997;278(10):858–863.

[n.a.], “Tobacco industry interference with tobacco control,” Geneva: World Health Organization (WHO), 2008.

NCI Monograph 17: Evaluating ASSIST – A Blueprint for Understanding State-level Tobacco Control Evaluation of American Stop Smoking Intervention Study for Cancer Prevention Chapter 8, Evaluating Tobacco Industry Tactics as a Counterforce to ASSIST (October 2006).

July 2022